In this Q & A, speech-language pathologist Chris Wing, PhD ’13, explains how language development is linked to attachment and emotional regulation. She also talks about encouraging children and adults to tell personal stories as a strategy to build their communication and executive functioning skills.

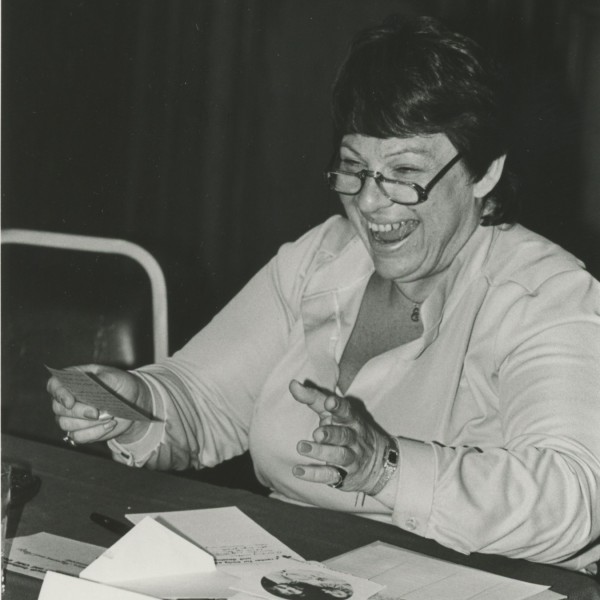

Chris Wing, PhD ’13, CCC-SLP, built on her career as a speech-language pathologist by pursuing a PhD in language development. She is currently developing a preschool curriculum that emphasizes communication. The curriculum was commissioned by The Family Partnership, a Minnesota nonprofit that provides early childhood education as well as mental health, home visiting, and other services. Wing is working with CEED evaluators Alyssa Meuwissen, PhD, and Mary McEathron, PhD, to evaluate the effectiveness of the curriculum, which is being piloted in preschool classrooms as well as in home visiting and parent education programs. In this Q & A, Wing shares information about the curriculum and about the science underlying its storytelling content.

What motivated you to pause your career and return to graduate school?

CW: I had been working with a population of young children at extremely high risk for speech and language delays. I observed that when we addressed these children’s communication needs, they were changing in ways that were not considered to be directly related to communication. I saw changes in self-regulation and executive functioning skills. I wasn’t familiar with how that worked. It moved me back to school for my PhD in speech-language-hearing science.

My total focus was to understand the relationship between overall development and communication. I had to merge separate sets of academic literature related to infant mental health and communication.

How is infant mental health related to language development?

Speech and language, attachment relationships, and executive functioning are all connected. Research shows that the ability to use internal state language is predictive of executive functioning. Internal state language is a speech pathology term. It refers to language like, “I wonder how you are feeling,” or, “I can see by the look on your face that you might be afraid.” In the infant mental health literature they call it “mind-mindedness”–being mindful of the child’s mental state.

In my research for my PhD, I found wonderful and fascinating information about how attachment is transmitted from caregiver to child. Parents with good executive functioning create secure relationships and are using this kind of language. The good news is that when we address children’s speech and language needs, we get spread across areas of child development that impact attachment and behavior.

How did the storytelling curriculum that you are designing come about?

John Till is senior vice president of strategy and innovation at The Family Partnership. He learned about the importance of executive functioning and self-regulation. He also learned about the need to develop a two-generation approach to strengthen these skills. We agreed that I would create a communication-based curriculum for both parents and children with personal storytelling as a key strategy. I wanted to get that process down to a concrete level: what does it look like? What does it sound like? What are the steps involved in helping children develop these skills?

The preschool storytelling curriculum is designed for direct delivery to children and also for parents to deliver to children. So one version is to be administered by preschool or child care teachers. The other version is to be used with parents either one-on-one in a home visiting context or in a group setting.

Often, the parents themselves have not had many opportunities to work on developing their own communication and self-regulation skills. We’ve actually gotten some data in from a pilot where we’re having home visitors listen to the parent’s narrative and prompt them with questions like “Who was there? When did it happen? Was there a problem? Was the problem solved? What was the sequence of events?” We saw changes in the parents in terms of how coherent their storytelling was. These skills don’t just happen on their own. They result from participating in interactions and from what we call scaffolding. Scaffolding means building on what they already know.

How does the curriculum build storytelling skills?

One of the major strategies is called “Telling My Story.” We don’t ask children to retell a story that they learned from a book or at school, such as a folk tale. Instead, we ask them to tell a story about their lives. In the academic literature, this is known as a personal narrative.

To determine the child’s skill level, we use a protocol where an adult shares an experience that involves getting sick or hurt. The adult then asks the children to share a similar experience. We’re not trying to upset them by asking about times when they got sick or hurt. We ask about these events because they have what we call emotional salience. Kids are at the top of their skill level when talking about these events. They show us everything they’ve got in terms of storytelling. That’s why sharing a story about a negative experience is part of the assessment process. But of course, the curriculum is not just about bringing up bad experiences. Throughout the curriculum, children have many opportunities to tell stories about a variety of events.

We help them tell their story by asking questions. We talk about words for physical states like hunger. We ask, “What were you thinking at the time?” Parents who really form secure attachments are conscious of their child’s mental state; they’re checking in and mirroring that.

After children finish telling their story, if they haven’t told us already, we ask, “How did you feel?” We ask this of both kids and adults. Some research shows that most of us adults really struggle with naming a feeling outside of some pretty concrete ones: happy, sad, afraid. We don’t get much better than that.

I recently went to a live recording of The Moth Radio Hour. Ten people told stories, and I was amazed at how few internal state words they used. To me, those are what connects us. I can’t really relate to the experience of someone who set a Guinness World Record canoeing on the Mississippi, but I can relate to how it made them feel. When we are able to name feelings, that ability correlates with emotional intelligence. So as parents practice naming their own and others’ feelings, that impacts their ability to engage with their kids.

A favorite definition of self-regulation I ran across that dovetails with what we’re trying to accomplish is, “Self-regulation is monitoring your internal states in relation to your external objective.” The regulating part comes in adjusting either your internal state or your external objective so that you have a match.

Our adult curriculum asks parents to tell their own story. It’s an opportunity to reflect, to problem solve, to process their internal state. With adults, we always end with an affirmation. We recognize something in their story that creates something coherent out of what can feel like chaos–many parents’ lives are chaotic. What we find in adult research on this kind of telling is that the important thing is not whether the storyteller felt successful in the story–it’s how they process it after the fact and see their own agency and what can be built on.

Your curriculum is currently being piloted. How is it going?

The curriculum is being simultaneously written, revised, and piloted. The original version was a six- to eight-week curriculum. Stakeholders gave us wonderful but sometimes painful feedback on that draft. One message that came through is that it needed to be a nine-month curriculum. The new version will last 30 weeks.

We did a “baby” pilot of the new version and found it was headed in the right direction. We were very encouraged, so we began our scheduled pilots at the beginning of the school year with 10 weeks of the curriculum complete. Now I’m writing ahead of the pilot. It feels like running in front of a speeding train, but there’s something about the content that has its own calming, mindful effect. Teachers have even said that the kids are being kinder to each other. One thing I like is hearing from teachers, “I like doing this. It’s fun. The kids like it.” That means it’s developmentally appropriate. We know neurologically that positive engagement facilitates learning. Fun is not optional; fun is mandatory!