By Mary Harrison, PhD, LICSW, IMH-E®

In the early days of 2020—a time that seems both recent and incredibly distant—I wrote a blog post about why Mr. Rogers still matters to people. The post seemed to resonate with readers at the time and has continued to do so during the upheaval of the past year. I’ve tried to think through why that might be, and I keep coming back to the idea of slowness.

You might have heard of the slow movement and related ideas like “slow food” and “slow work.” We’re often told we need to slow down, practice self care, check in with our loved ones, and find balance. This all sounds appealing, but at a time when we are inundated with news and images and updates and advice, it is difficult to actually slow down, to practice some of those coping strategies that are constantly pressed on us.

For some of us, the COVID-19 pandemic did enable—or enforce—a slower lifestyle. Some of us have found it possible for human connections to flourish over Zoom, even having regular conversations with friends and families in a way that we were never able to before. I can also recall some lovely moments of in-person connection, chatting with neighbors from afar or with fellow mask-wearers at the grocery store across a polite six feet of space.

But are we actually experiencing the physical sensation of slowness? Are our minds ever quiet? My body and mind seem to have forgotten what it means to slow down and just be, or to give something my full attention and let my mind wander in deep thought. Quiet nothingness is a time during which we can feel emotions, form new thoughts, slow our heart rates, make connections. But such slowness can seem very elusive.

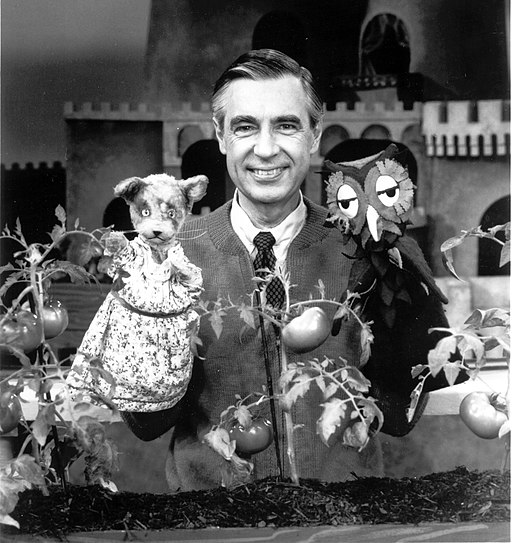

The beloved children’s TV personality Mr. Rogers moved at such a slow pace that it seems to me almost painfully so at times. In our world of clickbait, tweets, and text chains, connections happen quickly. And then we move on—quickly—to the next thing, and the next.

Mr. Rogers’ whole way of being was different. His well-known shoe-and-sweater-swapping routines were predictable and deliberate. The way he spoke allowed for words and ideas and questions to hang in the air for consideration. Frankly, watching old episodes initially drives me nuts. It’s the same as sitting for silent meditation after an absence of practice. It creates an instant need for mental list-making and physical fidgeting.

Sitting with an old Mr. Rogers episode is an invitation to visit a past version of ourselves. This past self didn’t always scramble to see who just texted or scroll to see who just posted. Perhaps this past self was five years old, home sick from school, and eating chicken noodle soup and saltines. This past self was comforted by a favorite Mr. Rogers Neighborhood episode in which he visited the crayon-making factory. Or perhaps this past self was the parent of a preschooler searching for something that their child could watch that didn’t involve a screeching cartoon character.

Watching Mr. Rogers is experiential learning for a more mindful, slower way of living. Start an episode as an adult and you will be reminded of familiar sights and songs. The nostalgia might feel sweet as you settle in for a whole episode.

But I wonder if at some point you will start to feel waves of a different kind of emotion. Urgency? Boredom? Irritation? Perhaps one of these labels will fit this itchy feeling, or maybe you’ll just experience it as a nagging “I need to be doing something” train of thought. When I tried this exercise recently, this was exactly what happened to me. Adding to my unease was a sense that I wasn’t proud of having these thoughts and feelings.

But like silent meditation or any mindfulness practice, there is a gap period before your body can actually slow down, before your mind can actually grow quieter. It’s uncomfortable. Other tasks beckon. Other things need tending. You tell yourself this is “good for you” because it’s a “healthy form of self-care.” You will yourself to sit and be quiet.

Here’s where I’ll advocate for watching Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood as a form of meditation. It works because he keeps you company; he talks and walks you through this uncomfortable gap period. Fred Rogers’ familiar routines and soothing cadence can dim our inner fluorescent lights and set the stage for the slowdown. Tolerating the transition from constant stimulation to slowness and silence is easier with Mr. Rogers, because he is already there. He is just ahead of you, waiting for you in that more intentional place. All you have to do is let go of the conscious or unconscious habit of responding to the call of half-finished tasks and buzzing notifications.

You can take the train to the land of make-believe, but in your case, it is from a place dominated by the crush of worries, tasks, and FOMO (fear of missing out) to a place of slowly untying shoes and zipping up sweaters. You can shed the layers of responsibility in favor of a safe learning experience. And all the while, your body can slow down, your mind can quiet, your heart beat can reset, and you can actually find yourself experiencing moments of just being.

Mr. Rogers can help us mind the gap between our fervent efforts at keeping our heads above water and living at a more natural pace. What are the benefits of slower living? For one, new ideas have space to come to light. We can experience a deeper level of exhale. Our human bodies can be open to the energy and light of others. Our children need this for learning; we need it for surviving and thriving.

I invite you to revisit Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood when you can. Observe yourself as you watch an episode: your mind, your heart, maybe your restlessness, maybe your longing for the next thing. I invite you to join Mr. Rogers for the full episode and see how you feel as it unfolds. See how you feel by the end. Transitioning to his slower pace just might remind you how it feels and leave you longing to experience such slowness again soon.