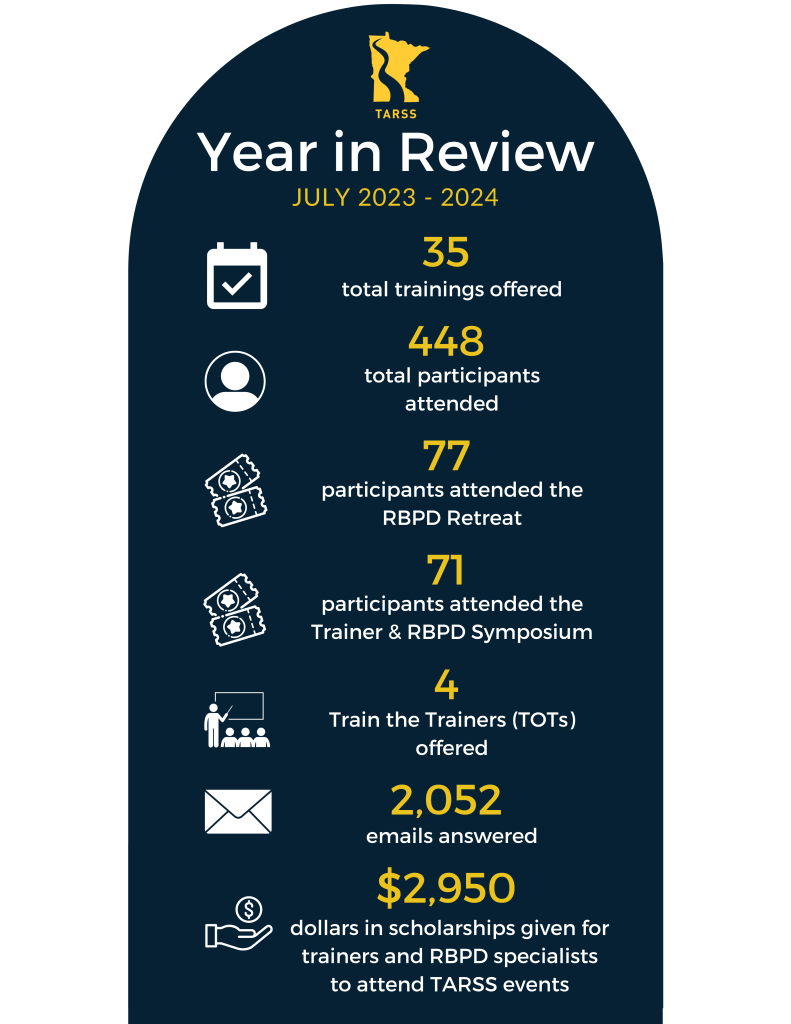

Take a look back at the past year of the TARSS program, and discover some of our activities by the numbers!

Take a look back at the past year of TARSS activities at a glance!

Take a look back at the past year of the TARSS program, and discover some of our activities by the numbers!

Trainers who are approved to train on DHS-owned SUID and AHT courses must attend a mandatory Zoom meeting to continue to train on these courses. Read the DHS memo and learn the details.

ATTENTION APPROVED TRAINERS ON DHS OWNED SUID and AHT COURSES:

The DHS-owned SUID and AHT courses have been reviewed and updated. In order to continue training this content in-person, we will be holding a required live, virtual trainer meeting on Zoom for trainers already approved on the courses and who continue to meet the trainer criteria. Trainers are expected to train the courses in-person for Child Care Aware. The meeting will be between 60-90 minutes and is offered at no-cost to you. Trainers will be expected to keep their cameras on during the meeting and there will be an online quiz at the end of the meeting. An 80% passing score will be required to continue to be approved on the course(s).

You are required to attend one of the following virtual sessions:

Please use this link to register for your preferred meeting time, the deadline for registration is Monday September 9. Refer to the memo from DHS (below) or contact tarss@umn.edu if you have any questions.

Storytelling/story acting is a special teaching strategy that harnesses the power of stories to help children build language and social-emotional skills. Download our tip sheets to learn more.

Our evidence-based tip sheets for early childhood professionals break topics down into two parts: theory (Introducing It) and practice (Applying It). This set of tip sheets explores storytelling/story acting as a way to help children build language and social-emotional skills. Many early childhood educators make use of stories in their classrooms, whether reading from a book or sharing stories spontaneously. Storytelling/story acting is a special teaching strategy that harnesses the educational power of stories. Our tip sheets explain how to do it and why it works.

Introducing It: Using Storytelling/Story Acting in the Early Childhood Classroom explains the strategy and the science behind it.

Applying It: Storytelling/Story Acting in the Early Childhood Classroom gives examples of how this strategy works in practice.

Below is a list of resources referenced in Introducing It: Using Storytelling/Story Acting in the Early Childhood Classroom.

Catch up on CEED staff’s latest presentations, accomplishments and honors!

Infant Mental Health Journal has named its top 10 most-cited papers, which include a study by Research Associates Alyssa Meuwissen, PhD, and Christopher Watson, PhD, IMH-E® (who retired from CEED in 2021). The paper that made the top 10 list is their 2021 article “Measuring the depth of reflection in reflective supervision/consultation sessions: initial validation of the Reflective Interaction Observation Scale (RIOS™).” Both Meuwissen and Watson were primary authors of the RIOS™. The RIOS™ is a tool that helps researchers study how reflective supervision works. It also helps them measure different aspects of a reflective supervision session. For this article, Meuwissen and Watson studied reflective consultation sessions attended by a sample group of child welfare workers. Their goal was to find out how well the RIOS captured the content of the sessions.

Deborah Ottman, who retired in June from her role as professional development coordinator, presented with Watson at the Minnesota Association for Children’s Mental Health (MACMH) annual conference on April 30, 2024. Their presentation was called “Who You Are Is as Important as What You Do: The RIOS™ Reflective Practice Framework.” The two explored how reflective practice skills are often less about “doing” than about “being”: being mindful, non-judgmental, curious, and empathetic, for example. One participant called the session “impactful and powerful” while another commented, “I had heard of reflective practice before but I wasn’t super knowledgeable about what it is all about. I appreciated the overview…and most importantly the kind and helpful demeanors of the presenters. They were truly inspiring to talk about a topic that asks us to challenge ourselves about what it is that is going on for us in such a calm and respectful way.”

The TARSS team organized the annual Trainer and RBPD Specialist Symposium which took place April 25-April 27, 2024, and drew more than 70 attendees. Participant comments included the following:

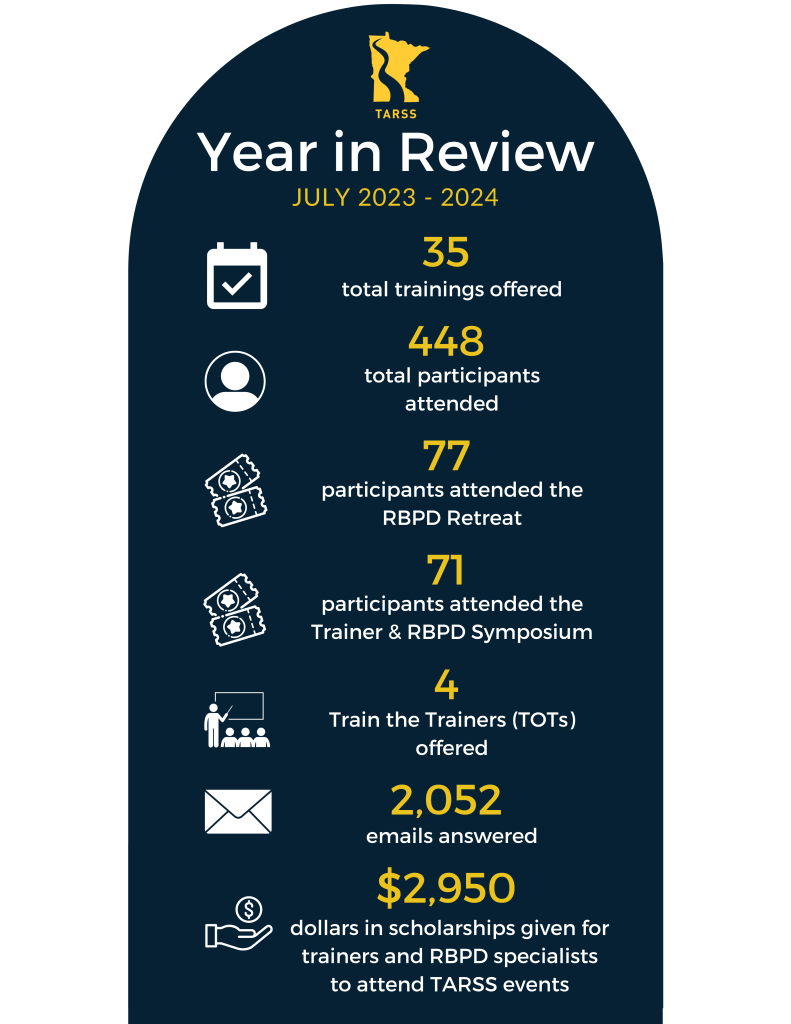

Ann Bailey, PhD, director of CEED, presented to the Minnesota Farm Bureau as part of its “Harvesting Solutions” webinar series on June 13, 2024. She presented on “The State of Child Care in Rural Minnesota,” describing the challenges facing the child care sector–as well as families seeking child care–in rural Minnesota. While there is a shortage of child care “slots” throughout the state, it is especially severe in greater Minnesota, where the past few years have seen a dramatic decline in the number of child care providers. In addition to describing the magnitude of the challenges, Bailey explained how access to quality early childhood education both improves children’s development and sustains the economy.

Curriculum Specialist Ashley Bonsen has held many roles in early childhood education, including teaching child development courses to adults. In her current role at CEED, she partners with the Department of Human Services to maintain a library of 300+ professional development courses.

TARSS Curriculum Specialist Ashley Bonsen joined CEED in July 2023. In this Q & A, she shares about her professional background teaching people of all ages, and she explains what people need to know about professional development for early childhood educators (ECEs) in Minnesota.

Can you talk a little about your professional background and how your career led you to CEED?

My first job out of college was as director of a Spanish immersion child care center. After that, I joined St. David’s Center for Child and Family Development as a care coordinator supporting children with disabilities and their families. Following that, I pivoted to teaching Spanish in public middle and high schools. I was teaching when the pandemic hit. That was a difficult time.

After the acute phase of the pandemic, I decided to explore teaching adults. I taught child development courses at St. Paul College, and I taught through a program from the YWCA of Minneapolis to help Early Childhood Educators (ECEs) obtain their Child Development Associate credential. In fact, I still teach at the YWCA. While I was teaching at these two locations, I also worked at an in-home child care program that a friend started. I worked every day of the week!

In July 2023, I was brought onto a project at CEED part time. I was hired to assist with the process of revising the Early Childhood Indicators of Progress (ECIPs), which are Minnesota’s early learning guidelines. I wanted to be part of updating the ECIPs because it is such an important and useful document. I used the ECIPs regularly with my YWCA and St. Paul College students.

The ECIPs project is ongoing, and in fall 2023, I transitioned into a full-time role at CEED taking on an additional set of responsibilities. As TARSS curriculum specialist, I work closely with Child Development Services, part of the state Department of Human Services (DHS). My job is to help maintain the DHS professional development curriculum library.

What does maintaining the curriculum library entail?

You could say I’m the keeper of the courses. DHS has a library of more than 300 professional development courses for ECEs. I work closely with Kami Alvarez, professional development policy specialist at DHS, to update and maintain those courses. That means compiling documentation on curriculum, tracking changes to the courses, and providing technical writing maintenance. I provide DHS with a curriculum delivery analysis as well. That analysis shows any gaps in the courses that are available. It states what the demands of the field are so we can address those needs. Additionally, I help determine when and how courses are revised.

How do you figure out the timing of revisions and how much to revise?

I look at the “expiration dates” for all of the courses that will be expiring in the next fiscal year. I then work with DHS to prioritize what courses need to be rewritten, what courses need updates, and what courses need to be retired. I look at a variety of data about each course: I look at course participation rates, I review feedback and suggestions from DHS partners such as Child Care Aware, and I also review feedback from trainers and participants. Trainers know course content backward and forward, so their perspective is very important. Participants have an opportunity after taking a DHS course to fill out a survey about the course and how the trainer did. Taking all of this data into account, I decide whether a course needs to be updated, or even completely rewritten.

What is the process for revising courses?

I make small revisions myself based on direct feedback, such as repairing broken links and correcting typos. For more substantial rewrites, DHS hires course writers. Keep in mind that many courses are offered in Spanish, Hmong, and Somali as well as English, so there’s a lot of work behind the scenes that goes into revisions. The state has a translation service and we’ve hired a translation firm to check our work over as well. Of course we want to make sure everything is translated accurately, but we also want to make sure the content is culturally appropriate. As an example, a course might talk about using utensils, but in a given community, hand feeding might be more appropriate. The challenge with translations is that from an equity standpoint, we want all DHS courses to be available in all the major languages spoken in Minnesota. From a logistical standpoint, though, that means DHS’ 300-plus courses are actually 1,200-plus courses.

In terms of the impact that revising a course can have, both the Active Supervision and Health and Safety courses were revised earlier this year. Both of these courses are licensing requirements. That means ECEs must take these courses in order to get and maintain a license to provide child care. As you can imagine, this means there is a lot of demand for these courses. It also means rewriting them was a big deal! It affected trainers as well as ECEs. Trainers who delivered the old courses needed to be trained to deliver the new ones. We call these events “trainings of trainers” (TOTs). A TOT is a training on how to deliver a particular DHS course.

What is the biggest area of growth for you in your position?

Getting familiar with the library of courses that DHS has to offer. I want to have information top-of-mind so that I can work more spontaneously rather than opening up documents and searching for information.

What would you like the public to know about professional development for ECEs?

One thing that can be confusing for people, myself included, is all the systems and organizations at play: state agencies, Develop, Achieve, TARSS, and so on. So sometimes, what we have to do is set aside the systems piece and just focus on the fact that in this state we value education. We want to be leaders in education, not just in K-12 but in early childhood. We believe in the importance of a wonderful and robust early childhood education. We want to make sure the professionals we are putting in those early childhood classrooms are equipped to handle whatever comes at them during their day. We want them to have the best possible training and information to do and sustain their jobs for as long as possible. Having high-quality, supportive professional development is a piece to help that. In Minnesota, we have a great catalog of courses that are provided, some at no cost, to ECEs. If an educator likes the idea of that, thinks that’s inspiring, and wants to be a part of it by becoming a trainer or a course writer, they can talk to me!

TARSS asked trainers what supplies they need for their work. Here’s what the 44 survey respondents said (scroll down for a text version of the infographic).

Play is more than just having a good time. Play helps children grow physically, cognitively, and socially. Download our tip sheets on the importance of play to learn more.

It’s easy to know play when you see it, but have you ever really thought about what defines an activity as play? Children engage in different kinds of play at different stages. Play is fun, but it’s so much more: it helps children learn and grow in many ways. Our evidence-based tip sheets for early childhood professionals break topics down into two parts: theory (Introducing It) and practice (Applying It). Introducing It: The Importance of Play in Early Childhood discusses various types of play. It also talks about the ways in which play supports children’s physical, cognitive, and social-emotional growth. Applying It: Incorporating Play to Support Learning and Early Childhood Development shares tips on setting up an environment that encourages children to take part in all kinds of play. Download these free resources below!

Don’t miss our other tip sheets on topics from authentic assessment to reflective listening! Have an idea for a topic you’d like to see? Email us!

Child care subsidies help qualifying families access high quality child care. New research shows that higher subsidy rates result in a better child care experience for these families.

New research shows that higher child care subsidies result in less disruption for families. Ann Bailey, PhD, director of CEED, and Elizabeth E. Davis, PhD, professor of applied economics, are leading a research project called Coordinated Evaluation of Minnesota’s Child Care Assistance Payment Policies. Bailey, Davis, and their colleagues are looking at recent changes to Minnesota’s Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP). These changes include higher child care subsidy payment rates. “Subsidy payment rate” means the amount that CCAP pays child care providers for their services to qualifying families. The researchers want to know how subsidy payment rates affect families’ access to high quality child care.

Not all child care providers accept subsidies. Sometimes, that’s because the payment rate is lower than what they usually charge. In Minnesota, providers can charge families the difference between the subsidy payment and their usual price. Higher subsidy payments, then, may expand the number of providers who accept subsidies. It may also mean that families end up paying a smaller share of the cost of care. Both of these factors can mean that families have more child care options, leading to a better child care experience for subsidized families.

Davis and co-author Jonathan Borowsky, JD, PhD, published new findings from the first phase of the research project. They looked at data about participation in the Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP) in Minnesota. They compared data from before and after changes in subsidy payment rates. They wanted to know if those changes would affect two things:

The size of the subsidy payment rate changes varied across counties in Minnesota. Davis and Borowsky compared the experiences of families in places where CCAP payment rates went up more with families in places that saw smaller increases in payment rates, or no increases at all. They found that higher subsidies improved both stability and continuity of care. Families who lived in counties with larger payment increases were significantly less likely to drop out of the subsidy program. They were also less likely to switch child care providers.

Stability and continuity matter. Stable relationships and predictable child care arrangements support children’s development and wellbeing. They also support parental employment. Frequent disruptions can have negative effects on both children and the adults who care for them.

Inhibitory control is one of our executive function skills. It’s the skill that allows us to resist an unhelpful impulse or a temptation. Children learn inhibitory control over time, like other executive function skills. Adults can help! Our latest tip sheets explain that music offers fun opportunities to practice inhibitory control.

Inhibitory control is one of our executive function skills. It’s the skill that allows us to consciously direct our behavior, instead of acting on autopilot. It’s also how we resist an unhelpful impulse or a temptation. Executive function researcher Adele Diamond writes, “[I]nhibitory control makes it possible for us to change and for us to choose how we react and how we behave rather than being unthinking creatures of habit” (Diamond, 2013).

Inhibitory control is hard to say. (Really. Try it!) It’s also hard to master–especially for young children! Children learn inhibitory control over time, like other executive function skills. They learn best with help from trusted adults in their lives. So how can we help children practice inhibitory control? Our latest set of tip sheets suggests one fun strategy: using music! We created these free resources in partnership with expert educators at MacPhail Center for Music. The tip sheets explain the theory behind inhibitory control. They also give practical tips on using music in your work with children.

Related: Don’t miss another set of tip sheets created in partnership with MacPhail: Introducing It: The Benefits of Music Integration to Emotional Regulation Development in Young Children and Applying It: Engaging in Musical Play with Young Children. Check out all of our tip sheets for more topics of relevance to early childhood educators.

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135-68. doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750

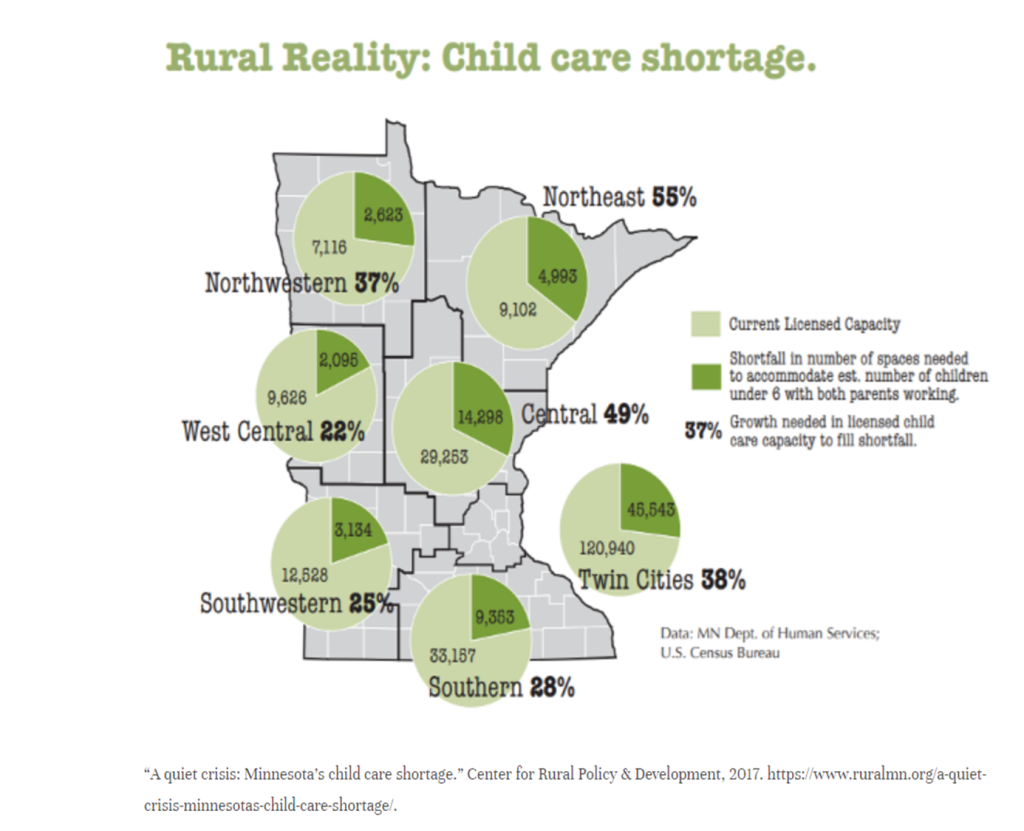

Early childhood educators and providers across Minnesota receive trainings that help them grow as professionals. The trainings are part of a large library maintained by Minnesota’s Department of Human Services (DHS). The people who lead these trainings go through their own trainings to learn how to do it. Those are called Trainings of Trainers (TOTs), and they are offered by the TARSS program at CEED.

Just recently, DHS updated its Active Supervision training, which is a very important required training for child care providers in Minnesota. 77 trainers applied to join the Active Supervision TOT in order to become approved to deliver this training. Learn more facts about this cohort of learners in the infographic below!

TARSS aims to establish a pool of trainers representative of the Minnesota population, with experience working with diverse communities and with the communities in which they live. Having a diverse cadre of trainers allows providers to access training near their homes and work and receive training from people who know their communities.