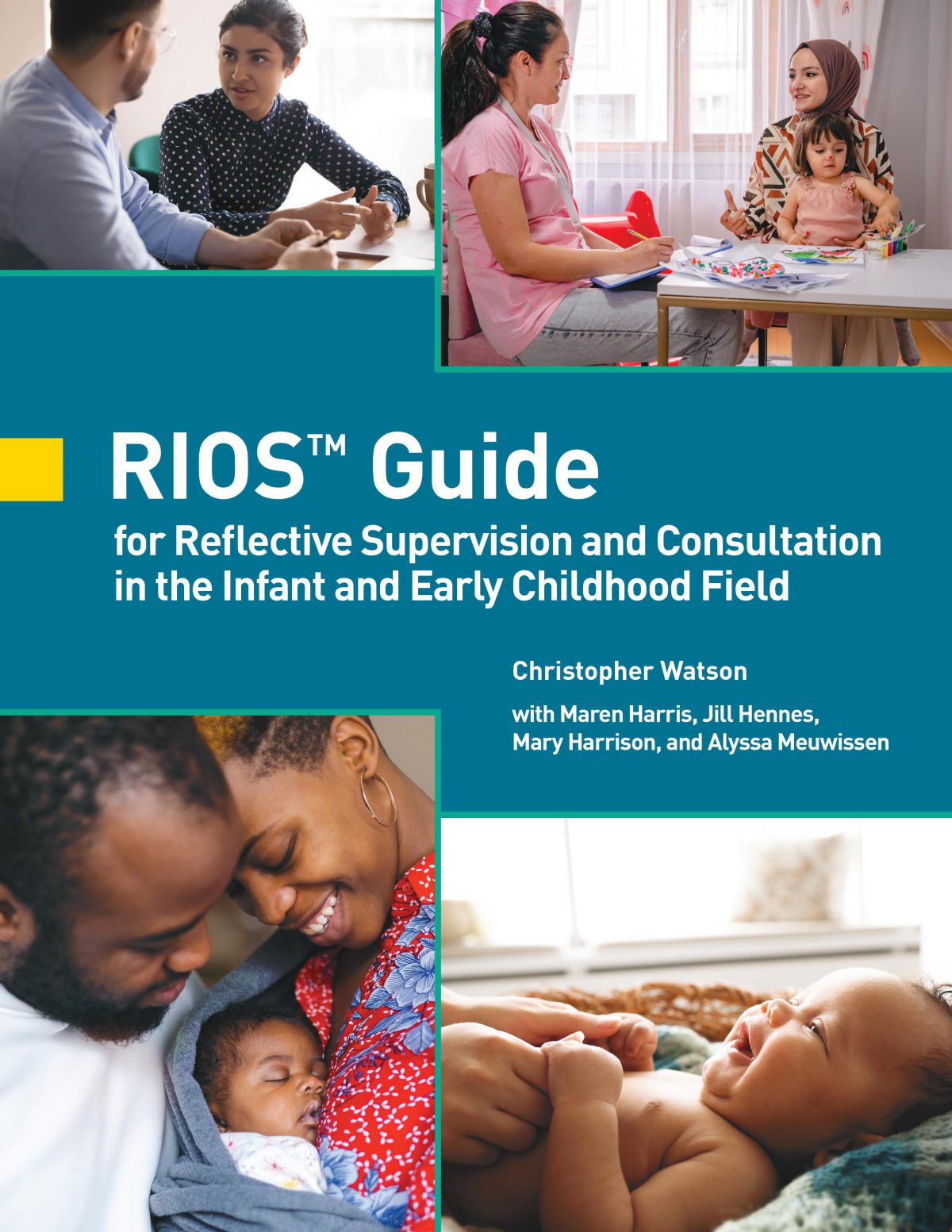

The RIOS™ Guide for Reflective Supervision and Consultation in the Infant and Early Childhood Field was recently published by Zero to Three. The book is the culmination of more than a decade of work by CEED’s Christopher Watson, PhD, Alyssa Meuwissen, PhD, and colleagues. Professional Development Coordinator Deborah Ottman was directly involved in preparing the Guide for publication. In this Q & A, Watson and Ottman shed light on the origin of the RIOS and discuss how the Guide was designed with applicability in mind.

How did the RIOS itself come about?

CW: Twelve years ago, at a meeting of the Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health, a group of us did an activity to try to understand the structure of a reflective supervision session. We came up with a process where five groups of people watched video recordings of reflective supervision sessions. We talked about our responses to what we saw and heard in the recordings, asking questions like, “Can we agree on what we’re seeing in this recording? What do we call it?”

That initial meeting gave us a bunch of data, and for the next eight years or so, a smaller group of us met once a month online to try to further distill the data, operationalize it, and fill it out. Here at the University of Minnesota, we did the final structuring to make that data into a scale that could be used in empirical research.

So the RIOS was intended as a tool for researchers to document and measure the “active ingredients” of a reflective supervision session. But it ended up being useful for practitioners, too.

CW: People immediately grabbed onto it as a way to explain reflective supervision when training both supervisors and supervisees. And supervisors began using it both prior to a reflective supervision session to remind themselves of what they wanted to address in the session, as well as following a session to review what occurred and to determine what they wanted to pursue in future sessions. It became a natural outgrowth. We created a RIOS Manual to train researchers to use the scale for their studies. Later, we decided to adapt the manual to create a how-to guide for practitioners who were using the RIOS as an aid in sessions.

In reality, though, the Guide is completely different from the manual. The manual taught researchers how to code recordings of sessions, in other words, how to put numbers on what they hear or observe and make some meaning of that. The Guide is for practitioners–supervisors and supervisees both, but particularly supervisors and their trainers. The Guide was shaped by input from practitioners around the country, so in it, you’ll read about real-life situations and professional relationships, and about using the RIOS framework to understand what’s happening in those situations.

DO: There are a couple of other ways in which the Guide was specifically created for practitioners in the field. First, there was an effort made to embed principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion into the Guide. This was the result not only of collecting the real-world examples that Christopher mentioned, but also of our current cultural moment in the wake of George Floyd’s death and other tragic instances of racialized violence. We received guidance from Dr. Barbara Stroud who, as a contributing editor for the Guide, focused on these issues in particular. She helped us be more specific about issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion in reflective supervision.

Also, the Guide includes a new tool to help practitioners who are using the RIOS as a job aid: a one-page Self Check form. It’s not an assessment; there’s no right or wrong. It’s a way for practitioners to track their growth and document what they tend to focus on in their sessions.

The Guide is the only book that explains how practitioners can use the RIOS in their jobs.

CW: That’s right. There are other excellent books about reflective supervision, of course. But our goal with the RIOS tool and with this book was to place reflective supervision within a framework with which to understand the processes involved.

DO: And to find ways to actively apply those processes, which are described in the RIOS as five Essential Elements and five Collaborative Tasks of reflective supervision.

But the RIOS is not a checklist, correct? People can’t just go down the list and say, “We addressed all the Collaborative Tasks.”

CW: There’s actually a disclaimer in the book about not using it as a checklist. You don’t have to hit each Essential Element and each Collaborative Task within a session. A given session may focus on one Essential Element, and that would be just fine. Although it’s not a checklist, the RIOS does provide a way for practitioners to look longitudinally or in a big picture way at an ongoing reflective conversation. For example, if I were tracking our conversations over a period of six months, and we never discussed Holding the Baby in Mind, that might be a problem and something we want to look at. We might say, “Well, this time we talked all about the parents’ problems, so in the next session, let’s talk about the baby and their experience.” Even though it may have been really important to talk about the adults’ challenges this time, ultimately you want to get to: “What does this mean for the child?”

DO: You may not be able to get to the child’s perspective until you address some of the things that are happening within the family or things that are coming up for the practitioner. The book is not prescriptive. “Guide” is the perfect word for it. It’s a roadmap that offers you a million different paths to the same destination: the child. And you can choose different paths on different days.

Go deeper with the RIOS with CEED’s online courses, RIOS™ 1: Using the RIOS™ Framework for Reflective Supervision and RIOS™ 2: Advanced Reflective Supervision Using the RIOS™ Framework, starting soon!